| |

|

|

||

|

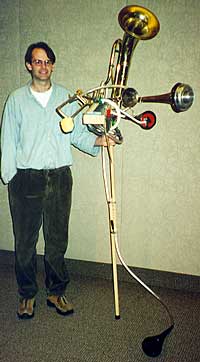

What does a composer do when an instrument cant express the sounds in his head? For Richard Johnson; the answer was easy - build his own instrument, dubbed the winslaphones. Not only can he more fully express his musical ideas, but in Johnsons current role as a traveling teacher and composer the winslaphones has been invaluable in introducing his audience to new music. The visually striking instrument is as unique as the name (deriving from Johnsons middle name, Winslow), and allows for endless musical variations. As fascinating as the winslaphones is, however, for Johnson it is only a part of his ongoing musical development.

The winslaphones combines parts of a euphonium, trombone, trumpet, and melodica; a bassoon reed and trumpet and trombone mouthpieces; whistles; and a worms nest of PVC tubing and connectors to form sort of a mutant one-man-band. This might initially seem like quite a departure for a composer of "serious" music, yet Johnson notes that developing new instruments has broadened his range in the more traditional composing medium: "It forces you to think about sound in a whole different way. Its a completely different world than what composers are used to." Johnson considers himself foremost a composer; building instruments is only a hobby (though "a very time-consuming one"). His first efforts, made primarily from PVC pipe, were experiments in creating new tones. "It was mostly just a fascination with sound, I think," Johnson says of his initial motivation. "Thats where the new instruments came from." The Instrument's History

Much as the design of the winslaphones evolved during its creation, so too has its use evolved. Johnson says that one of the primary uses of the winslaphones is as a teaching tool, something he had not anticipated. "Kids love it," he says. "Generally one of the hardest things is getting them interested in music, but when they see this, they cant wait to find out what it does. And from there, theyre much more receptive to learning about and trying other things." Playing the Winslaphones Even to learn for ensemble playing, however, the winslaphones poses a great challenge.The instrument has five bells, each with a different set of slide positions. "Physically, thats a lot to learn," notes Johnson. And even when the physical positions are learned, patterning the mind to remember the different placements and sounds they produce is an ongoing process. Johnson recognizes that the difficulty in learning the instrument will likely dissuade anyone else from learning to play it, especially since the time needed to create the instrument destines it to remain one of a kind. Its uniqueness has led some people to consider the winslaphones a novelty - although most listeners are intrigued by Johnsons creation, a few dismiss it as an updated version of the traditional one-man-band. Johnson admits the validity of this comparison, but makes one important distinction: "The only difference is in approach. I look at it from a serious compositional point of view, not as a novelty."

Composing for the Winslaphones Of course, this does not mean others cannot enjoy the music. Johnson has found that even though he is not yet as proficient as he would like to be, his audience is still receptive. "People are interested in hearing something new, even if I havent played particularly well," he says. As Johnson becomes more familiar with the instrument, he hopes others will want to write music for the winslaphones; a colleague of his currently is working on a piece. Future Plans Hell keep practicing the winslaphones, however, if only as an outlet to let off some steam. "Thats really the best part - just goofing off, making weird sounds," he says with a grin. Johnsons sentiment sums up the winslaphones (if anything can) - a blend of the serious and the whimsical, versatile enough for almost any purpose. And that, when combined with Johnsons creativity and inventive bent, promises a bright future for new and experimental music. Play the winslaphones! | Winslaphones home | Winslaphones slideshow | Resources

|

||||

© Copyright 1999, Minnesota Public Radio. |